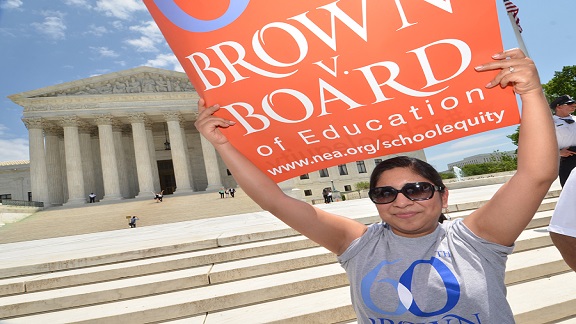

WASHINGTON (NNPA) – In 1954, Lucinda Todd was one of 13 plaintiffs in the landmark Brown v. Board of Education Supreme Court case that declared “separate but equal” unconstitutional. Last week, her granddaughter Lucinda Noches Talbert, stood on the steps of Supreme Court and continued making the argument for equal public education under the law.

“I’ve seen what happens to communities when schools are closed. What once was the heart of the community becomes a rotting eyesore of the community, forcing children to faraway schools,” she told a crowd of parents, students, labor union members, activists, and concerned citizens who had gathered to rally for what they called educational justice. “To my grandmother, the Brown case was about equality, access to opportunity, and access to the American Dream. We still have not realized my grandmother’s dream.”

Speakers included American Federation of Teachers President Randi Weingarten, National Education Association President, Dennis Van Roekel, and Delegate Eleanor Holmes Norton (D.C.).

In the 60 years since Brown, a perfect storm of factors has eroded public education, most visibly through school closings and the charter school boom, particularly in communities of color. As of fall 2014 in New Orleans, for example, all but five of the city’s 89 public schools have been closed or converted to charters. Houston has closed 32 public schools since 2003. Washington, D.C. has closed 39 since 2008. Chicago closed 49 public schools last year alone, and 111 in total since 2001.

The case against closings is presented — and the storm of factors dissected — in a new report titled “Death by a Thousand Cuts.” It is presented by Journey for Justice Alliance, a national network of 36 grassroots organizations led by parents, youth, and ordinary community members working for community-driven school improvement.

“This is institutional racism … and Journey for Justice is your mirror,” said Jitu Brown, national director of Journey for Justice Alliance, as he officially released the report during the rally. “We will not sit by while you steal our schools, and steal our children. This is not going to be a report that’s going to sit on somebody’s desk. This report is going to be backed by boots on the ground.”

The report points out that charter schools were intended to be community-based alternatives, but instead have manifested as corporate franchises.

“The core premise of charter schools was that they were to be given increased freedom from rules and regulations in exchange for improves academic achievement and yet we now have over 20 years of data demonstrating that they are no more effective, on average, than public schools, (even if we judge them by the extremely-limited, standardized-test-based metrics they prefer),” it states.

There’s also the trend toward charters refusing special education, disabled, and English-language-learning students. In 2012 the Government Accountability Office (GAO) reported that charter schools were enrolling significantly less children with these characteristics and that about half of charter schools reported having insufficient resources to serve students with disabilities.

Charters usually appear in communities of color, using public dollars and competing with established public schools. Charters promise newer facilities and alternative education methods, and public school enrollment falls.

Detroit Public Schools, for example, is the district serving the highest ratio of children of color in the country, according to the report (98 percent of students). Between 2005 and 2012, enrollment has fallen 63 percent; at the same time, area charter schools saw an enrollment increase of 53 percent.

In the Houston Independent School District, where 92 percent of students are of color, enrollment is down only 11 percent—but charter schools have seen a nearly 200 percent increase in students.

According to the report, lack of enrollment is one of three common reasons for closing a public school; bBudget cuts and low academic performance are the other two reasons.

Neighborhood school closures often affect the surrounding community.

“Residents lose community services housed in schools, such as pre-K programs, before- and after-school programming, adult education classes, and health clinics,” the report explains. “Property values in the neighborhood often declines, residents moves away, and new residents become much harder to attract because a boarded-up school is a sure sign of neighborhood instability and deterioration.”

Jacqueline Edwards, a mother and grandmother from Newark, N.J., who travelled to the rally by bus with approximately 75 other parents and community members, has felt these effects.

“Our students have to go into communities they don’t know, and it’s dangerous. We have a lot of sex offenders in our area, abandoned buildings, and dangerous traffic,” she explains. Newark has closed 13 schools in five years, with 11 more expected, according to the report. Edwards’ 12-year-old daughter and 9 year-old son attend Newark public schools.

“When they closed the 15th Avenue School, my two kids were in that school, and were diverted to [South 17th Street School], which was a significant distance from my home,” she says. “We relocated so their school was just around the block, but what if next year it’s going to be something different? My daughter will have to go two miles walking to school. It’s not fair.”

The students themselves were front and center at the rally, both at the makeshift podium and in the crowd.

Aquila Griffin was one of several teens who took to the microphone to rail against the school closings that affected her attendance at Dyett High School in Chicago. Griffin described having to take the mandatory physical education and art classes online, being without college-prep Advanced Placement classes, and having only two years of Spanish to choose from while better-resourced schools studied Spanish, French, Mandarin, and German, and enjoy music and art classes.

Students from organizations across the country were also present, such as Boston Area Youth Organizing Project, which seeks to promote social change through social and political youth empowerment. Kaylia Green, a high school senior and member of the BYOP, felt her public school education had been inadequate.

“I’m from Miami, and the schools there are worse. Boston schools are not as [segregated], but their education is off. I’m a senior and I don’t feel prepared for college,” she shared. “I feel like I’m being spoon-fed. I’m going to go to college and do what I’ve got to do because education is everything, but…I’ll just go to my resources and get the help I need.”

Her friend Andy Juerakhan was also present, despite being, in her words, “pushed out” of school.

Juerakhan, who has been trying to resume his education, says he was repeatedly (and unfairly) suspended from school, which led to chronic truancy on his part. With his record and dwindling public school options (Boston has closed 18 schools in the last six years), he is unable to find a school that will allow him to enroll.

“When you don’t come to school enough, the school basically forces you to drop out. Since I’m a push-out, getting back into school has been one big process. Sometimes schools won’t take you just because you’ve been out,” he says. “I’ve tried the Re-Engagement Center but there’s only so much they can do. I have to get a lawyer … I’ve been to three [school] interviews, and they didn’t accept me. It’s not school anymore, it’s like prison.”