They say everything in sports is forgiven of winners, from Kobe Bryant and Ben Roethlisberger all the way back to Ty Cobb. But the story of the halo that has come to rest upon the head of Ray Lewis is more than that. The man defies explanation and logic.

In June 2000 Fulton County Superior Court Judge Alice D. Bonner approved a deal allowing Lewis to avoid murder charges and jail time by pleading guilty to misdemeanor obstruction of justice. Lewis was sentenced to 12 months’ probation, the maximum sentence for a first-time offender. As part of his sentence he agreed to testify against two co-defendants who were eventually found not guilty of murder as well.

To this day, no one has served time for the stabbing deaths of 24-year-old Richard Lollar and 21-year-old Jacinth Baker.

When Lewis’ plea agreement was handed down, Sports Illustrated published a story that included a couple interesting details.

“Fulton County District Attorney Paul Howard refused to say how the plea agreement was brokered but said his office made the right decision to prosecute Lewis,” the article detailed.

“‘A trial is an instrument to reach the truth, and I think that in many respects it has been shielded,’ Howard said. ‘We are continuing to try to bring the truth forward.’

Those words are telling.

More telling has been the reaction Lewis has received since the trial.

The story goes that in training camp the year after the trial, legendary tight end Shannon Sharpe, who was then playing for the Ravens, took Lewis aside and told him that the only way to redeem himself was to be spectacular on the field — to play so well that people might forgive and forget what happened months earlier.

And it worked.

Lewis went on to win Super Bowl XXXV MVP honors, Defensive Player of the Year, was a unanimous All-Pro selection at middle linebacker and was named a starter in the Pro Bowl. His regular-season total of 136 tackles led the Ravens, and he added 31 tackles, two interceptions, nine pass deflections, one fumble recovery and a touchdown in the four-game playoff run.

As a team that season, the Ravens set single-season records for fewest points allowed, with 165, and fewest rushing yards allowed, with 970. They also produced four shutouts, one shy of the single-season record. The Ravens finished first league-wide in six key defensive categories.

Sure, after winning the Super Bowl the signature “I’m going to Disney World!” line was given to Trent Dilfer instead of Lewis, but nearly ubiquitous and almost immediate forgiveness was granted by a news media and public that are notoriously thirsty for a star to tear down.

Today, the National Football League – the same league that fined Lewis $250,000 in 2001 for what then-commissioner Paul Tagliabue called his “unlawful obstruction related to a very serious occurrence” – is rumored to be considering Lewis as an adviser to Commissioner Roger Goodell after he steps off the playing field for the final time.

Goodell called Lewis, “a tremendous voice of reason” earlier this year.

“He’s someone that has a unique pulse of the players and that’s helpful to me,” Godell said. “That perspective is important to hear, and he would always share that with me whether he called or I called him … He means a great deal to this commissioner, and I could tell you that I will always seek out his input.”

This is a man whose sins don’t just include a possible double homicide in 2001. Lewis has also been publicly accused – though never convicted – of violence in several previous incidents, including two involving separate women who were pregnant with his child while he was at the University of Miami (one woman declined to press charges after the police arrived, while the other reportedly complained that the police had hindered the investigation, which was eventually dropped after the Miami-Dade state attorney’s office concluded it lacked sufficient evidence to pursue the case), according to the Daily Beast.

And New England Patriots wide receiver Wes Welker’s wife recently reminded us all, “6 kids 4 wives. Acquitted for murder. Paid a family off. Yay! What a hall of fame player! A true role model!” [sic].

The discussion about Lewis is one that would be profoundly different if he played baseball.

There, the sanctimonious writers wring their hands at any conceived affront to the sanctity of the game. This is a group of men so high in their ivory towers that they have refused admission to the Hall of Fame to the game’s all-time leader in hits and home runs because of personal failings.

But football is different.

We see football players and baseball players differently for two main reasons. First, most distinguished baseball analysts are journalists rather than former players. Second, football is so much more physically taxing and daunting that journalists often defer or soften their judgments because they understand that they could never in a million years do what these men do for a living.

Baseball, it seems, is a working man’s occupation in which all who are privileged to be affixed to the stat sheet are judged. Football, on the other hand, is a battle of gladiators and to question anything besides their effort is to blaspheme in a house of piety.

In a world of blood sport combatants, Ray Lewis is the ultimate warrior.

He is a leader who has the magnetism of a Baptist preacher and the tenacity of a starving man fighting to the death for one last meal.

During a Ravens game years ago, Phil Simms told a story that during a practice he’d seen Lewis angry at his teammates because he was the only one chasing a receiver who had broken free from the defense and was about to score a touchdown. Lewis told every member of the defense do 100 pushups. And they did it. All of them.

Lots of guys spout platitudes about God and winning and leaving it all on the field, but somehow after 17 years in the game Lewis manages to make all of us stand up and believe. It’s not so much inspiring as it is implausible.

His “glory to God” and “no weapon formed against this team shall prosper” rhetoric has been heard before from athletes at the top and bottom of every sport and at every position. But there’s something different about Ray.

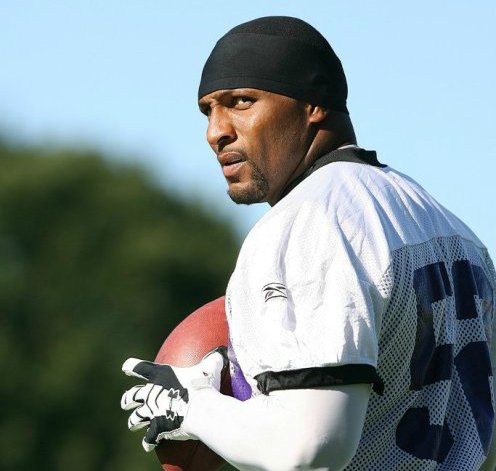

Middle linebacker isn’t a glamorous position, but every time the Ravens play, before, during and after the game, we wanted to know where number 52 was and what he was doing. Whether he was dancing, tackling or preaching, Ray Lewis gave it everything. He wore his heart on his sleeve and he never for a second seemed jaded, self-aggrandizing or cynical.

His ability to defy age, not just by playing at the highest level but by maintaining an unquestioned leadership of the Baltimore Ravens, from the front office to the practice squad, has been unrivaled by anyone in recent memory. But that’s not what has washed away his sins.

We love Ray Lewis because we understand that what we all got to watch him do was special. Because he was bigger than football.