by Jennifer Porter Gore, Word In Black

Overview:

Baltimore’s Group Violence Reduction Strategy is credited for the sharp reductions in crime and could be a model for other cities.

On April 29, 2015, when mistrust between Baltimore police and the Black community boiled over after Freddie Gray was fatally injured in the back of a police van, Brandon Scott was an ambitious young city councilman, looking to help tackle the city’s public safety problems. It was no small task.

Clashes in the streets between protesters, angry at Gray’s death, and police, already under significant pressure to bring rising crime under control, put a national spotlight on Baltimore’s problems with poverty, race, and gun violence. That year, the city recorded 344 homicides, the second-highest in its history.

That day, “I was on the City Council and was actually preparing to introduce legislation about unsafe police arrests” when he heard the news about Gray, Scott tells Word In Black. “So, yes — I know exactly where I was that day.”

Turning Point

What a difference a decade has made. Scott is now Baltimore’s dynamic, 41-year-old mayor, and protests over Gray’s death marked a turning point for the city — one that led to a surprising improvement in relations between the community and law enforcement. And the number of homicides has plunged to a near record low.

“We wanted to approach this in a way that didn’t leave gun control and violence reduction solely as a responsibility of law enforcement.”

Baltimore mayor brandon scott

The turnaround, experts say, came after Scott, who won office in 2020, had a series of huddles with representatives from the Baltimore Police Department and the state prosecutor’s office, thinking through how to stop crime and gun violence. The result of those meetings was a new policy: the Group Violence Reduction Strategy.

Using a combination of services — everything from job training and employment opportunities to mental health counseling and housing access — the group came up with a long-term strategy: make it clear to individuals known to have a high likelihood of engaging in criminal activity that they would need to change behavior. Then, help them find ways to make that change.

The strategy first focused on the city’s crime hot spots, pulling in the Maryland Attorney General’s Office, along with city-based service providers Roca and Youth Advocate Programs, Inc. The organizations then set about helping the at-risk residents find jobs, housing and counseling — anything they needed to stop illegal behaviors.

Housing, Jobs, Counseling, and Hope

“We wanted to approach this in a way that didn’t leave gun control and violence reduction solely as a responsibility of law enforcement,” Scott says.

A life coach was assigned to the high-risk participants to help them gain job training, get a GED, find housing, or even get a driver’s license and open a bank account. Baltimore’s Department of Public Works and other agencies stepped up to hire the trained individuals.

That same year, Baltimore sent a message showing it was serious about gun control when it sued Polymer80, a company that manufactures untraceable “ghost guns” that flooded the city. The lawsuit was settled for $1.2 million in February 2024.

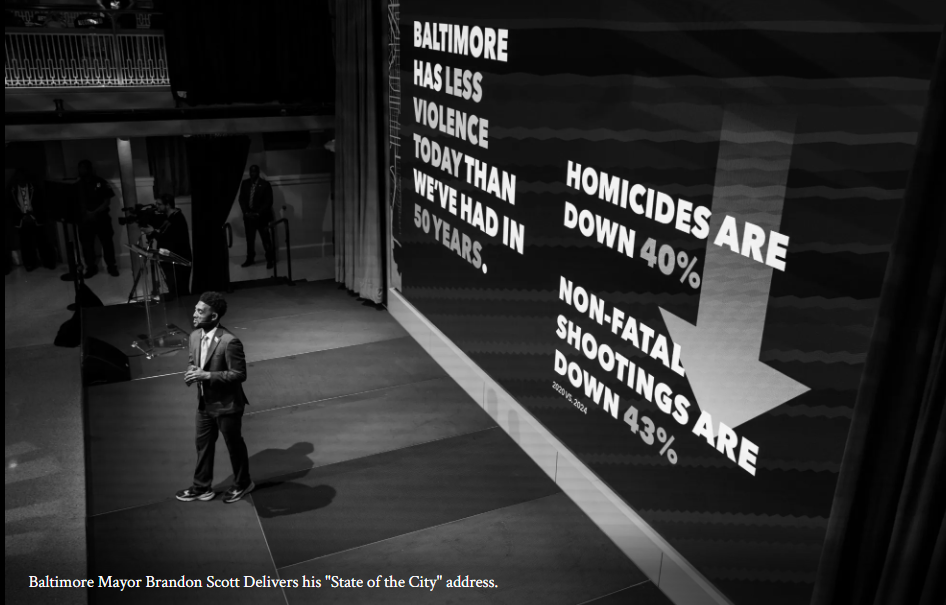

By 2024, the strategy began to pay dividends: at year’s end, the city had recorded 201 homicides, a 40% decline and the lowest number of deaths since 2020, according to police data. Non-fatal shootings also dropped 43% over that same period.

Model for Other Cities

A University of Pennsylvania study found that Baltimore’s GVRS had markedly reduced crime in target areas. Yet the regions where the strategy wasn’t being used showed no increase in crime.

Continued investment in community partnerships and tailored support services, and focused deterrence on high-risk residents shows promise.

“Over 200 Baltimoreans at the highest risk of being involved in group violence have received life coaching and other wraparound services as part of this strategy,” according to Scott’s office. Among participants, nearly all of them stayed away from crime — either as perpetrators or as victims.

Other cities grappling with crime, like Memphis and Cleveland, have reached out to the Baltimore mayor to find ways to replicate this success.

“GVRS has played a critically important role in driving the largest year-over-year homicide reduction in Baltimore’s history … and is showcasing that our comprehensive approach to reducing gun violence is working,” the mayor said.