The following article is the first of a four-part series spotlighting Atlanta’s rich social scene, prior to the meteoric success of hip-hop and other mediums, including the rise of Tyler Perry as an international movie mogul. The series targets Atlanta’s social scene circa 1960 thru 1990. Enjoy and be educated about a wonderful era, way before Atlanta became the “ATL”. Veteran music writer Timothy Cox offers his personal insight about a unique period in our city’s rich music history.

While Black Atlanta’s current entertainment climate is chock-full-of hip-hop family values, mogul recording artists and movie studios , it should be chronicled that less than 30 years ago – Atlanta’s music scene was way different. Then, the scene was foundationally based on home-grown natives whose social world consisted of small-town attitudes with down-home, Southern values with folks dressing-up, looking to paint the town, void of drama and criminal elements.

In recent conversations with several mature-age native Atlantans and city residents who’ve lived in the city during the past few decades, the Atlanta Constitution-Journal is offering a reflection of Black Atlanta social life from days-gone-by, prior to the 1980s revolution now known as hip-hop culture.

In conversation, many of the same bars and lounges tend to be identified in the process of recalling the good-ole-days. Below, names of the following nightclubs have surfaced throughout conversations with many participants of this article.

For instance:

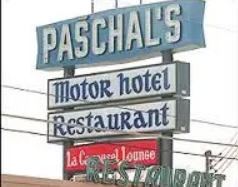

In West Atlanta, Paschal’s Hotel showcased jazz inside La Carrousel Lounge; In Southwest Atlanta (SWATS) on Campbellton Road: Mr. V’s Figure 8, Cisco’s, Marko’s, Regal Room, The Limelight, Blue Dolphin, Ellerie’s, American Legion, Copacabanna; In College Park, on Old National Highway: 20 Grand, Talisman’s, Grown Folks, Crow’s Nest; In DeKalb County, Decatur: Chit-Chats, Harriston’s, Faces, Café Eschelon; Downtown Atlanta/Underground Atlanta: Scarlet O’Hara’s, A-Train; Apothecary Lounge; In Virginia Highlands: Walter Mitty’s and Blind Willie’s; West End Atlanta: Living Room Lounge, Late Edition, Club Palladium in Bankhead; Marietta: Club Deion’s became Club 21; Buckhead: Club 112 was first located on Roswell Road, later moved to Piedmont Avenue, Diamond Club was next door to the second Club 112, Fat Tuesdays, Dante’s Down The Hatch, Havana Club, Johnny’s Hideaway and Café 290; Downtown Atlanta: Mr. V’s on Peachtree, Atlanta Nights became Dominique’s, both on Peachtree Street; Barley’s Billiards, Apache Café, Churchill Grounds jazz room, also on Peachtree Street next door to the Fox Theater; On West Peachtree Street, San Souci was originally a white-oriented disco club, but after several performances, Atlanta’s Third World Band helped integrate the room, becoming one of the first black bands to play San Souci – ultimately San Souci became a predominately black nightclub; Strip Clubs and its many deejays, are vital to Atlanta’s music scene, including Magic City, Blue Flame, Gold Club and Cheetah’s I,II and III.

Does current Reality TV and Tyler Perry’s influence, somewhat disregard old-school Atlanta’s contributions?

In direct response to the current wave of reality TV shows which regularly offer a mecca-like view of Atlanta, the Rev. Dr. Herman “Skip” Mason Jr. has created a special website which provides locals a more realistic view of living in Atlanta in the new millennium, and an optional forum to comment and reflect on the “good ol’ days.”

“The intent of my Facebook page,‘Vanishing Black Atlanta History’ is to provide a space to share and relish the rich history of Black Atlanta, including our neighborhoods, schools, churches, social organizations, the Atlanta University Center, civil rights, politics and entertainment,” said Dr. Mason.

Dr. Mason, a Morris Brown College graduate and Atlanta native, has lingering ties to his high school alma mater, Therrell High Class of ’80. “I believe that some of the reality shows reflecting Atlanta does not fully represent the richness of the city’s history, heritage and present-day reality. The Real Housewives of Atlanta features two natives Kandi (Burress) and Porsha (Williams), but their lifestyles are of a certain socio-economic base and may not fully show a proper representation of Black Atlanta. NeNe

Concerning Tyler Perry’s sudden and overarching impact in the city, Dr. Mason responds to Perry’s creative success and how it relates to the average native Atlantan, as such:

“I am certain that many of Mr. Perry’s shows may display a slice of life for some Atlantans depending on their lens and where they come from.” He adds that it’s difficult to measure who’s an average native Atlantan, mainly because natives derive from varying socioeconomic backgrounds, including public housing projects, middle-class homes or apartment lifestyles – it crosses all class barriers,” said the pastor of Atlanta’s West Mitchell Street Christian Methodist Episcopal (CME) Church.

Anita Stephens Floyd, 66, is an Atlanta native who grew up in what’s affectionately known as the Fourth Ward. She’s from the Grady Homes public housing projects and graduated from David T. Howard High School in 1971. She says the city that’s depicted on reality TV shows and in some Tyler Perry productions, is not the images she recalls from her youth.

“The Atlanta I see on TV is not the Atlanta I grew up with. I see the nonsense on TV, I rarely watch it,” says the grandmother of five. She fondly recalls the nightlife scene that existed when she was in her 20s. She recalls working the night-shift at Grady Hospital and meeting up with co-workers at places like Marko’s and Mr. V’s Figure 8 on Campbellton Road. “The whole scene has changed since then,” she said. “Seems like we were more sophisticated and mature than many of today’s young adults,” she added.

At age 14, she also recalls paying her respect at Dr. King’s funeral services at Ebenezer Baptist Church in April 1968.

“I rubbed shoulders with so many major celebrities that day, mainly Robert Kennedy, Harry Belafonte and Dick Gregory,” she recalls. “[Dr. King] was from my neighborhood, but that’s when it hit me on how major of a figure he was,” she said.

Dr. King and colleagues were rumored to have often met at places like Paschal’s to develop civil rights strategies

It’s often been noted by various native Atlantans that Dr. King and his closest colleagues would congregate at Paschal’s Hotel or at the Living Room Lounge in West Atlanta, to conjure civil rights strategies over delectable soul food items and choice beverages.

John Robertson, leader of the John Robertson Quartet, said jazz was a preferable music taste for Dr. King and his contemporaries. Located in the heart of the Atlanta University Center zone, the Living Room Lounge on Simpson Road near Mason-Turner Blvd., was owned by Rufus “Charlie Boy” Turner aka “Dad” – by close friends and patrons. Living Room would easily be categorized as a “chitlin-circuit” operation, Robertson said.

The late Harold “Smoove-Daddy Rap” Johnson, was a retired Atlanta firefighter, but a legendary, mature hip-hop artist who worked on recording deals with Turner, according to sources. Johnson, a Savannah native and Morris Brown product, was also an athlete, musician and actor. He was also a “regular” at the

Living Room Lounge throughout the 1990s, and a consistent contributor of Jack “The Rapper” Music Conventions, founded by former WERD-Atlanta radio pioneer, “Jockey” Jack Gibson.

Even in the 1990s, Living Room Lounge was an old-school soul music room that featured live bands and dee-jays and the cover-charge was low, Robertson recalls, “but the dress-code was upscale. Mainly older gents dressed to the nines, because they were of a by-gone era of the late 1960s and 70s. Colorful suits with matching shoes – and Stetson hats – reflective of Blaxsploitation films like the Dolemite, Rudy Ray Moore -type movies,” said Robertson. Though he hails from Florence, S.C., Robertson’s jazz expertise was well-received by local aficionados, who eagerly attended his nightly sessions at Dante’s Down The Hatch at Underground Atlanta and in Buckhead, after he assumed the lead-gig following the death of Dante’s original bandleader Paul Mitchell.

“This was another Atlanta, before Mayor Maynard Jackson transitioned it to be an International city.” says Robertson, 62, an accomplished acoustic pianist who flipped-on his soulful Jimmy Smith-styled blues chops when gigging on the club-owned Hammond B-3 organ inside the Living Room.

“During that era in the early ‘70s through the early 1990s, Atlanta’s nightlife was run by men like Charlie Cato, Henry Wynn, Eddie Ellis, Frank Matthews and Bumpy Johnson. They could have been classified as hustlers, but mainly they were all interested in promoting live bands throughout the city,” said Robertson. “And that was a good thing, especially for the black musicians and patrons,” he added.

Reggie Ward, 71, is currently the guitarist for both the SOS Band and Fred Wesley’s New JB’s. He fondly recalls arriving on the Atlanta scene in 1972 from his native Albany, Ga. Early exposure to the city’s many jam sessions provided unknown musicians (like himself) a chance to expose their wares, while bar patrons were entertained by witnessing ongoing new talent arriving on the scene, he said.

Ward notes that Underground Atlanta was largely an entertainment complex, until a fire, in the early 1980s – destroyed the original essence of Underground Atlanta. When it re-opened around 1990, it was mostly a retail shopping district. Ward recalls performing at Underground’s Scarlet O’Hara’s in the sixties.

David Heath, 60, recalls seeing Archie Bell & The Drells at Scarlet O’Hara’s – “it was a real classy joint,” said Mr. Heath, a record producer and Augusta bandleader of the Perfect Picture soul Band.

Tim Sanders, 75, also of Augusta, remembers his freshman year at Morehouse College (1965) when he and some of his fellow first-year Maroon Tigers, visited Paschal’s Le Carrousel Lounge. “I saw jazz greats Yusef Lateef and Joe Henderson there, after painting a moustache on my face,” he laughingly recalls. Sanders, a saxophonist, later performed regularly at Scarlet O’Hara’s in the mid-1970s, with the Cortez Greer Band. The venue was owned by Marvin and Julie Adelman, he recalls. Sanders was also a frequent visitor to Churchill Grounds, the cozy jazz spot once located next door to the Fox Theater.

Newton Collier, 75, was a talented trumpeter who played gigs in his native Macon with the likes of Sam & Dave, Rufus Thomas, Eddie Floyd and Percy Sledge. He too concurs that the music scene has changed drastically in the past 40-plus years.

“I would walk down Hunter Street (later, renamed Martin Luther King Jr. Drive), and across the street from Paschal’s was the Continental Club. I was new at Morris Brown, but at night, I started playing with my cousin, Otis Collier and the Continentals on the weekends. Lester Maddox, who later became Georgia’s governor, owned a small restaurant-club near there, but wouldn’t hire blacks to play his room. Around that time, I joined SNCC and became a student political activist – doing sit-ins, etc. Soon, I quit college and moved to Augusta to play with Leroy Lloyd and the Swingin’ Dukes.” Collier, a math major at Morris Brown, moved to Boston and landed day jobs with MIT and Honeywell, as a research technician. While playing night gigs at Boston’s legendary Sugar Shack Lounge, owned by Rudy Guarino, Collier survived a near-fatal gunshot to the face in 1975 during a mugging, which slowed his music career. He eventually relocated back to his native Macon, where he currently lives