By Austin Sarat, Amherst College

Photo: Ali Lapetina / NBC News

Fresh evidence of the nastiness and divisiveness of the 2020 presidential election emerges every day.

President Trump has let loose a storm of invective over Twitter about various African American public figures and about the conditions of life in America’s inner cities. The president seems bent on exploiting a rural/urban divide and creating racial cleavage as a way to get re-elected.

In addition, he has questioned the patriotism of Democrats and alleged that they are trying to “destroy our country.”

Democrats have responded by denouncing the president’s racially tinged language and accusing the president and his supporters of being the ones destroying the country.

“Four years of Donald Trump,” former Vice President Joe Biden claims, “would be an aberration in American history. Eight years will fundamentally change who we are as a nation.” Biden, of course, is running for president.

Nasty, divisive elections are nothing new in the United States. As someone who teaches and writes about the importance of historical memory in American law and politics, I believe the 2020 election will rival the ugliest America has ever witnessed.

AP/John Minchillo

There are lessons that can be learned from examining this election’s parallels with two previous presidential elections – 1860 and 1968 – both of which left America deeply divided.

Slavery and geography in 1860

In the lead-up to the 1860 election, the nation was splintered by the question of slavery and by geography, with sectional conflicts between the more industrial northern states from the more agrarian South.

Those divisions produced a schism among Democrats and the formation of two separate parties. Stephen Douglas led the anti-slavery Northern Democrats, and John Breckenridge led the pro-slavery Southern Democrats as their candidates for president.

Library of Congress/Mathew Brady’s Studio, between 1844 and 1860

A third party,the Constitutional Union Party, nominated John Bell. It was a splinter party composed of disillusioned Democrats and former members of the Whig party (a major political party in the mid-19th century which stood for protective tariffs, national banking, and federal aid for internal improvements). The Constitutional Union Party wanted to avoid secession over slavery. Bell’s

battle cry was “The Union as it is, and the Constitution as it is.”

Abraham Lincoln, an opponent of slavery, was the Republican candidate. Yet he promised to let the South hold onto its slaves so long as slavery was not extended to any new territories.

“Wrong as we think slavery is,” Lincoln said, “we can yet afford to let it alone where it is… but can we, while our votes will prevent it, allow it to spread into the National Territories, and to overrun us here in these Free States? If our sense of duty forbids this, then let us stand by our duty, fearlessly and effectively.”

Despite winning the election, whites allied with the Southern Democratic Party did not see Lincoln as a legitimate president because of his opposition to the expansion of slavery and perceived hostility to the beliefs and values of Southerners.

Seven Southern states seceded between Lincoln’s election and inauguration: South Carolina, Mississippi, Florida, Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana and Texas.

Lincoln regarded secession as illegal.

Rather than waiting for Lincoln’s Union troops to act, the newly named Confederate States attacked Fort Sumter, a Union fort in Charleston, South Carolina. Thus began the Civil War, in which an estimated 620,000 soldiers were killed, nearly 2% of the U.S. population.

Bitterness in 1968

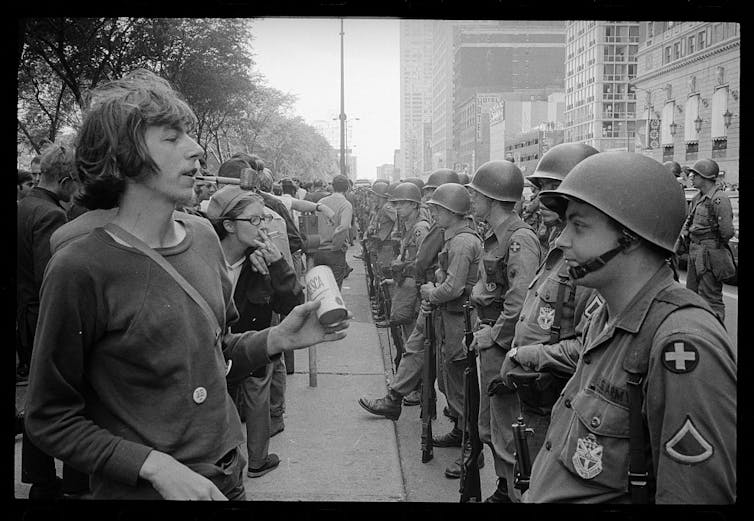

A little more than 100 years later, the 1968 election was marked by extraordinary bitterness arising from the Vietnam War, the legacy of the assassinations of Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert F. Kennedy, and a backlash against the ongoing civil rights revolution.

As was the case in 1860 and is the case now, race was at the center of the 1968 campaign.

In 1968, Republicans nominated Richard Nixon, who relied on a “Southern Strategy” that used opposition to desegregation and barely concealed racist appeals to “law and order” to enlist the support of white Southerners.

Nixon also stirred up resentment by appealing to what he called “the great silent majority.”

“There are two kinds of Americans,” Nixon said, “the ordinary middle-class folks with the white picket fence who play by the rules and pay their taxes and don’t protest and the people who basically come from the left.”

Like today’s Democratic Party, in which some candidates are calling for revolutionary changes while others offer only reform, the Democrats of 50 years ago had to choose among candidates with starkly different visions of the future of their party and the nation.

The Democrats fractured over the Vietnam War with their division on display during the nominating convention. They chose the establishment candidate, Vice President Hubert Humphrey, as their standard bearer.

Library of Congress/Leffler, Warren K., photographer

Today the leading contender for the Democratic nomination for president is yet another establishment candidate and a former vice president – Joe Biden.

In 1968, Segregationist Gov. George Wallace of Alabama, a Democrat well-known for his declaration “segregation now, segregation tomorrow, segregation forever,” ran a third party campaign for president.

Wallace promoted what The New York Times called a “visceral populism” and used raucous rallies to belittle his opponents. He asked his supporters to “Stand Up for America.”

Wallace received 13.5% of the vote. He carried five Southern states – Alabama, Arkansas, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi – and almost won enough votes to throw the election to the House of Representatives to decide.

Like the aftermath of the 1860 election, 1968 created what columnist and author Michael A. Cohen called “a very clear racial divide between the two parties” and a sharp division about the role of the federal government in American life.

Since his entrance into national politics, President Trump has borrowed from both Nixon and Wallace, sometimes using the same rallying cries. Thus, in 2016 his campaign handed out signs at his rallies, “The Silent Majority Stands with Trump.” And he skillfully evokes the populism of Wallace’s “Stand Up for America” when he promises to “Make America Great Again.”

‘A house divided’

In the 1860 and 1968 elections, arguments about race and appeals to racial resentment were used in ways that injured America. The current campaign is lining up to be a repeat performance.

The 1860 and 1968 elections also offer warnings that the vitriol surrounding an election can leave the losing side feeling that it cannot reconcile with those who prevailed and the winning side angry even after its victory. Such vitriol, I believe, is the daily grist of the politics on both sides of the 2020 campaign.

In fact, like the Southerners of 1860, people in both parties now question the legitimacy of their opposition. Because of President Trump’s alleged collusion with Russians, the fact he lost the popular vote and his race baiting a majority of 18- to 30-year-olds, many liberal commentators and prominent Democrats like U.S. Rep. John Lewis and former President Jimmy Carter call him an “illegitimate president.”

And, if a Democrat wins in 2020, some leaders of that party worry that the president will not accept defeat and will contest the election in court. Liberal commentators predict that “the defeated Trump will be on Fox News and Twitter every day saying that the election was stolen from him and that the Democrat is not really the president.”

As the country faces the prospect of a rancorous 2020 presidential election, the elections of 1860 and 1968 should remind all Americans of Lincoln’s prophetic warning that “a house divided against itself cannot stand.”

[ Like what you’ve read? Want more? Sign up for The Conversation’s daily newsletter. ]![]()

Austin Sarat, Professor of Jurisprudence and Political Science, Amherst College

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.