Editor’s Note: This is article nine of an 11-part series on Race in America – Past and Present, sponsored by the Kellogg Foundation.

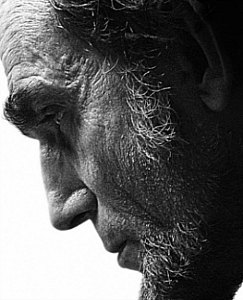

The opening scene of Steven Spielberg’s cinemythic portrait of the sixteenth president features President Abraham Lincoln seated on a stage, half cloaked in darkness, and observing the Union forces he is sending into battle. It’s an apt metaphor for the man himself-both visible and obscure, inside the tempest yet somehow above the fray. Lincoln was released in early November, 2012 just in time to shape our discussions of January 1, 2013, the 150th anniversary of the Emancipation Proclamation.

In fairness, this narrative of Lincoln’s Civil War, equal parts cavalry and Calvary, did not originate with Spielberg. The legend of the Great Emancipator began even as Lincoln lay dying in a boardinghouse across from Ford’s Theater that night in April 1865 in the same way that JFK’s mythic standing as a civil rights stalwart was born at Dealey Plaza in November 1963.

History is malleable. There is always the temptation to remake the past in the contours that are most comforting to us. In a nation tasked with reconciling its democratic ideals with the reality of slavery, Lincoln has become a Rorschach test of sorts. What we see when we look at him says as much about ourselves as it does about him. And what we see, or choose to see, most often is a figure of unimpeachable moral standing who allows Americans to gaze at ourselves in the mirror of history and smile.

If the half-life for this kind of unblemished heroism is limited — we’ve grown more cynical across the board — it has remained resonant enough for our politicians today to profit from their association with it. The signal achievement of Spielberg’s Lincoln is the renovation of that vision of Lincoln, a makeover for a nation that had elected its first black president to a second term just three days before the film hit theaters.

Beyond the obvious, though, lies a deeper theme between Obama and Lincoln: the identities of both men are inextricably bound to questions of both disunity and progress in this country. It’s worth recalling that Obama’s rise to prominence was a product of his 2004 speech to the Democratic National Convention, in which he offered a compelling, if Photoshopped, vision of a United States where there are no red states or blue states, where neither race nor religion nor ideology can undermine national unity.

On the 150th anniversary of the Emancipation Proclamation, we see unwitting testimony to our ongoing racial quagmire in the reductive ways we discuss the author of that document and the reasons for slavery’s end. We speak volumes about our impasses in the glib, self-congratulatory way we discuss the election of the president most ostensibly tied to Lincoln’s legacy.

It’s important to note that Spielberg’s film about the death of slavery all but ignores the Proclamation. That choice allowed the director-and his audience-to avoid both Lincoln’s support for the mass colonization of free blacks and also the fact that the now-hallowed Proclamation left nearly a million slaves in chains. It also made unnecessary any discussion of the uncomfortable truth that the Proclamation was devised in part as a war measure to ensure the loyalties of border states and deprive the Confederacy of its labor force, while leaving open the question of the South getting those very slaves back, should they return to the Union.

Instead, Spielberg’s Lincoln centers on the comparatively clean moral lines surrounding the Thirteenth Amendment. But like a great deal of the popular ideas about Lincoln, the film confuses the president’s strategic ideas with his moral ones, and in so doing shifts the landscape toward redemption.

The strategic and moral benefits of Lincoln’s actions are not mutually exclusive, but the need for a redemption figure makes us behave as if they are. The fact that Black freedom occurred because a particular set of national interests aligned with ending slavery doesn’t diminish the moral importance of it. Indeed, the moral high ground here is that Lincoln, unlike millions of Americans in both the South and the North, was able to recognize that slavery was not more important than the Union itself.

This seems somehow insufficient to the definition of heroism today, but it shouldn’t. The by-product of our modern, mythical Lincoln is that he allows us to shift our gaze to one American who ended slavery rather than the millions who perpetuated and defended it. By lionizing Lincoln, we are able to concentrate on the death of an evil institution rather than its ongoing legacy. The paradox is that Lincoln’s death enabled later generations to impatiently wonder when Black people would cease fixating on slavery and just get over it.

When Obama cast himself in the mold of Lincoln in 2007, he could not have known how deeply he would find himself mired in the metaphor. As a recent Pew Study revealed, our country is more divided along partisan lines today than at any point since they’ve been conducting studies. Basic demographic divisions — gender, race, ethnicity, religion, and class — do not predict differences in values more than they have in the past.

Men and women, Whites, Blacks, and Hispanics, the highly religious and the less religious, and those with more and less education differ in many respects, but those differences have not grown in recent years, and for the most part they pale in comparison to the overwhelming partisan divide we see today.

This is only partly because of the growth of cable news programs offering relentless blue-versus-red commentary and a la carte current events. It’s also because party identity has become a stand-in for all the other distinctions the study explained.

That chasm is the stepchild of the sectionalism of Lincoln’s era. Today, we are another House Divided, though the lines are now drawn more haphazardly. And this is where Obama and Lincoln part ways. In future feature films about the current era, it won’t be the details of the president’s life that will be redacted, but the details of our own. More specifically, it will be the details of those Americans who greeted Obama’s re-election with secession petitions; those who reacted to the 2008 election by organizing themselves and parading racially inflammatory banners in the nation’s capital; those who sought solace from demagogues and billionaire conspiracy theorists who demanded that a sitting president prove his own citizenship.

To be clear, though, something in the nation has changed. At no point prior to 2008 could a presidential aspiration have been so effectively yoked to this yearning for a clear racial conscience. But beneath the high-blown, premature rhetoric of postracialism lies the less inspirational fact that those changes were as much about math as they were about morality.

Depending on your perspective, we have either reached a point of racial maturity that facilitated the election of an African-American president or we’ve reached a point where a supermajority of Black voters, a large majority of Latino and Asian ones, and a minority of White people are capable of winning a presidential election. Again, these ideas need not be mutually exclusive, but the need for clean lines and easy redemption makes us behave as if they are.

Indeed, the real problem is not that the nation has so consistently sought balm for its racial wounds, and drafted Lincoln-and Obama-for those purposes; it’s the belief that we could be absolved from the past so cheaply. No Lincoln, not even an unfailingly moral one who was killed in service of a righteous cause, could serve as an antidote for ills that persisted, and continue to persist, for a century and a half after his demise. We find ourselves now in circumstances where actual elements of

racial progress are jeopardized precisely because we’ve smugly accepted the idea of ourselves as racially progressive.

The Thirteenth Amendment states that “[n]either slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction.” We are a nation in which a Black president holds office while more than half a million duly convicted Black men populate the prisons and county and municipal jails hold hundreds of thousands more. The symbolic ideal of postracialism masks a Supreme Court that undermined affirmative action in higher education and the preclearance clause of the Voting Rights Act.

The election of an African-American president is a watershed in our history. But the takeaway is that what we do during these moments is somehow smaller than what we do between them, that our heroes are no better than we are, nor do they need to be. Harriet Tubman is often cited as saying she could have freed more blacks if only she’d been able to convince them they were slaves. In our own era, the only impediment to realizing the creed of “We Shall Overcome” is the narcotic belief that we already have.

Jelani Cobb is the author of “The Substance of Hope: Barack Obama and the Paradox of Progress” and the director of the Institute for African-American Studies at the University of Connecticut. This article was originally published by the Washington Monthly Magazine.