(CNN) — I have never met Nelson Mandela, but we have had many conversations.

In my family’s tiny shack in Nairobi’s Kibera slum, my one-way exchanges with the great man kept me going. Mandela survived 27 years of prison; maybe I would make it out, too.

Mandela became South Africa’s first black president in 1994, when I was 10 years old. In Kibera, people celebrated and talk circulated the streets about this man, but I didn’t see how his story connected to mine until much later. I was struggling too hard simply to survive.

At 10, I was on and off the streets. I flitted from house to house, unable to live at home with my mother because my stepfather had threatened to kill us both if I tried to come home. I knew I was born poor, and believed I was fated to die poor. This was my prison.

I needed a role model, but in Kibera, these were in short supply. At 16, I felt the pressure from gangs and drugs — while fighting the temptation to drink my misery away and to find temporary comfort with women, like I saw my friends do.

Even as the shadow of AIDS spread, I saw no reason not to die young, because I had nothing to live for.

Our lives in the slums seemed to take a friend every day. Police shot my friend Boi; they thought he looked like a criminal. My childhood friend Calvin hanged himself. His suicide note said what I felt: “I just can’t take it anymore.” Both of my sisters were raped and impregnated as teenagers. People seemed to fade and disappear. To live was the exception. I am now 29, and all but two of my closest childhood friends are dead.

It was Mandela who saved my life.

A visiting American gave me two books. I had never gone to formal schools, but I had learned to read and write with the help of a kind priest. The American gave me a collection of speeches by the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. and Mandela’s “Long Walk to Freedom.” It was Mandela’s book that spoke to me. I couldn’t put it down. Here was someone whose life I could somehow picture.

For the first time in my life I saw I had a choice. I could either submit to the degradations of poverty, to the prevailing hopelessness, or I could start my own long walk.

I started small, using 20 cents from my pay at a factory job to buy a soccer ball. I organized young people to work together in an organization that has grown to include a school for girls, a health clinic and a community services project. This year we will serve 50,000 people. Yet as I look at the larger structural problems of urban poverty in my country, I feel my work has just begun.

Despite my doubts and concerns, I would begin and end every day with a private conversation with Mandela. I’d ask him what he’d do when his problems seemed insurmountable.

I shared with him my triumphs, and I read every speech of his I could find.

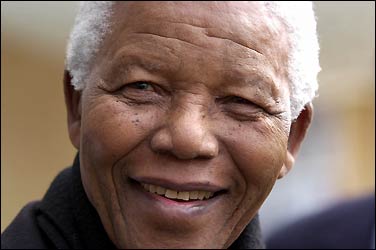

But as I grew older I began to wonder about the power and perils of being a living hero. Mandela was, for me and for my continent, more than a person. He is the emblem of progress. He came through poverty and struggle yet did not allow it to embitter him. Instead he seemed emboldened by a sense of urgency.

My fear is that we become too comfortable with his legacy — content with honoring what Mandela has stood for that we forget to carry forward his sense of urgency.

The journey to freedom in my country, Kenya, and in Mandela’s own country, South Africa, is far from over. On a recent visit to Johannesburg, I spoke for an hour with three young men about the crushing challenges of their lives in one of South Africa’s burgeoning slums.

They are not alone. Mandela accomplished so much, but worldwide an ever-growing gap between rich and poor and mounting inequality threatens all for which he fought.

I still talk to Mandela, and I wonder what he might do today. How he might organize another movement to take Africa forward. These are conversations we must all begin to have.

As we begin to anticipate his loss, so too we must celebrate the need for a next generation of selfless and driven leaders. For me, Mandela’s example will always stand as a reminder of what is possible when conviction faces injustice, of the work that still remains unfinished, and of the long road ahead.

Editor’s note: Kennedy Odede is the president and CEO of Shining Hope for Communities, a nonprofit organization that fights gender inequality and extreme poverty in the Kibera slum of Nairobi, Kenya. He is a 2013 New Voices Fellow at the Aspen Institute.

The opinions expressed in this commentary are solely those of Kennedy Odede.