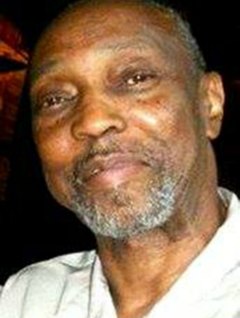

Every day Richard Green, 67, wakes up in pain. He creeps over to the edge of the bed and sets his feet down, bracing himself for the day ahead. First are the pangs of putting each leg into his slacks. Then, he undergoes the torment of sliding each arm into his shirt. Even lacing his shoes, something he has done since childhood, is a test of strength. Often he’ll take ibuprofen before willing his knees and back to lower his body into the car and withstand the painful drive to work as an administrative temp worker.

About seven years ago, Green was diagnosed with degenerative disc disease, the breakdown, bulging, or tearing in the spine’s flexible cartilage discs, as well as the narrowing of the spinal canal that houses the spinal cord. The worn discs put pressure on the spinal cord and surrounding nerves, which leads to chronic pain and nerve damage.

“You learn to cope,” he explained. “You just have to move; it’s worse if you don’t. By the end of the day, I’m completely exhausted from coping with the pain. When I get home I just go to bed. Sleep becomes your only relief.”

And that’s only if his sleep apnea and GERD (a severe form of acid reflux) are tolerable enough to let him get a good night’s rest. Fortunately, his lifelong asthma and heart condition rarely give him any trouble.

Green, who is uninsured and ineligible for Medicaid, can afford neither a doctor’s visit nor the resulting treatments or prescriptions. According to his home state of Georgia, his monthly income – $850 by his account, and inexplicably around $2,000 by theirs – is enough to afford healthcare without the assistance of Medicaid, the federal insurance program for low-income families and individuals.

Green is one of 48 million Americans currently living without insurance in the United States, according to the Census Bureau. Of those, 7 million are non-elderly African Americans. Green’s age qualifies him for Medicare, though he doesn’t have it yet—if he opts in next year, he expects to pay a $150 annual deductible, plus incidental charges.

Without the benefit of Medicaid or Medicare, he will have to pay an insurance company directly for medical coverage. With the start of open enrollment for health insurance exchanges under the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, Green might be able to get insured and access the care he needs.

Within the first year of the Care Act’s enforcement 14 million previously uninsured Americans are expected to enroll.

At the time of his diagnosis, Green was insured through his wife’s employment. Insurance paid for a $100,000 surgery, recovery, and medication, and he was seeing a neurologist. Even with the insurance though, his healthcare costs began to climb.

“Cost of care became such an issue I couldn’t continue [treatment]. It was an insurance problem, because you have out-of-pocket costs that come along with it,” he explained.

When his wife’s job downsized, his access to healthcare evaporated. And that’s why he is excited about President Obama’s signature health care plan.

According to Census data, 10.9 million African Americans today are living below the poverty level and most simply can’t afford even basic coverage. Although 68 percent of uninsured African Americans work, it’s usually in low-paying jobs that either don’t offer insurance benefits, or don’t pay well enough to cover the associated out-of-pocket costs of employer-sponsored coverage, such as co-pays, premiums, and deductibles.

The Affordable Care Act caters to uninsured and underserved populations in several ways. For starters, insurance companies will no longer be able to deny coverage to those with preexisting conditions, a major issue that has long been a barrier to getting insured. The law also creates an easy-to-understand marketplace where people can compare the prices and packages offered by already-existing private insurance companies, all at once.

Theoretically, this ability to get legally mandated transparent, accurate quotes from several insurance companies, simultaneously, will force the companies to lower their premium prices to compete for buyers. A person can then choose from an array of affordable insurance plans, using federal- or state-run call centers or websites to access the marketplace.

Low-income citizens who are unable to afford the least-expensive plan offered by the companies in their state will be eligible for federal subsidies (to pay for insurance), or tax penalty waivers.

This is where Medicaid steps in. Medicaid, which was created and built into the Social Security system in 1965, is intended to act as a healthcare safety net for low-income individuals and families with children. Originally, the Affordable Care Act called for states to expand Medicaid eligibility to those who make less than 138 percent of the federal poverty level. Today, that’s $15,857 per year for a single person, and $38,047 per year for a family of five.

But last year, as a result of Supreme Court case National Federation of Independent Businesses v. Sebelius, the Medicaid expansion provision was made optional for states Currently, 24 states and the District of Columbia have enacted the Medicaid expansion, 15 have rejected the expansion—including Richard Green’s home state, Georgia—and 11 states are currently undecided.

According to the Kaiser Family Foundation, in the states that aren’t expanding 5.2 million adults – 6 in 10 uninsured African Americans – are expected to fall into the gap between the original Medicaid eligibility standards and the least-expensive insurance coverage premiums.

Kansas City CARE Clinic, formerly Kansas City Free, is located in Missouri where Medicaid won’t be expanded. It’s one of the largest free clinics in the country, funded primarily through government grants and donated goods and services. Although patients are asked to make a $10 donation on every visit, no one is turned away for inability to pay or documentation status.

Kansas City CARE Clinic service area straddles both Kansas and Missouri—the latter having rejected the expansion, and the former remaining undecided. Kansas and Missouri have been at legislative odds before. In the years leading up to the Civil War, Kansas was a newly minted territory preparing to join the Union as a free state, which threatened Missouri’s slavery economy as well as the fragile balance between slave and free state representatives in Congress.

Of course, the Medicaid expansion probably won’t lead to another “Bleeding Kansas,” but there will be winners and losers when Kansas makes its decision. Although the state seems to be leaning toward rejecting the expansion, Kansas City CARE Clinic and other healthcare providers could end up with a split; expanded Medicaid would cover most of their patients residing in Kansas, while their patients from Missouri will fall into the coverage gap.

Because of this uncertainty, the clinic is implementing a billing system for the first time in their 43 years, so that they are equipped to serve those who are able to receive Medicaid or enroll in the marketplace and purchase insurance. Instead of the good-faith $10 donation, all patients will pay via income-based sliding scale, Medicaid, or insurance.

“We felt we had no choice,” says Dennis Dunmyer, vice president of community services at Kansas City CARE Clinic. “We wanted them to expand [Medicaid], but we feel like we don’t want to turn away the people who can get it because we can’t accept their insurance. We don’t want to turn anyone away. But it’s a different dynamic to say, ‘Here’s your bill’ instead of ‘Are you able to donate $10?’”

Richard Green lives in Clayton County, Ga.. In April, Georgia Governor Nathan Deal told a Fox News host that the Affordable Care Act “was a train wreck about to happen.” In a video made public by the Georgia Democratic Party, Georgia Insurance Commissioner Ralph Hudgens tells an audience, “The problem is Obamacare. We’ve got to now determine what we can do to solve that problem. Let me tell you what we’re doing – everything in our power to be an obstructionist.”

And that doesn’t help Richard Green.

“I’m hopeful but doubtful that I will be able to get insurance, because…I’m here with a governor who has decided to be totally uncooperative,” he said. “I’ll probably have to check the federal market. Everyone deserves affordable healthcare. Hopefully [the reform] will help me, but more importantly, all those who need coverage and medical care.”