Editor’s Note: This is article VIII of 11-part series on race in America – past and present, sponsored by the Kellogg Foundation.

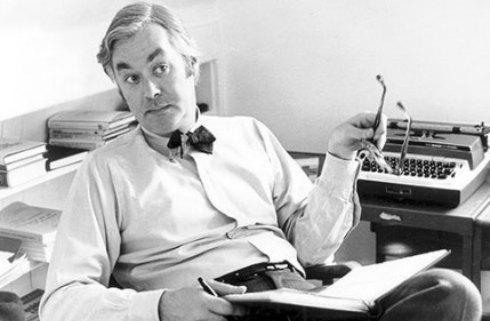

In 1965, Daniel Patrick Moynihan released a controversial report written for his then boss, President Lyndon Johnson. Entitled “The Negro Family: The Case for National Action,” it described the condition of lower-income African-American families and catalyzed a highly acrimonious, decades-long debate about Black culture and family values in America.

The report cited a series of staggering statistics showing high rates of divorce, unwed child-bearing, and single motherhood among Black families. “The white family has achieved a high degree of stability and is maintaining that stability,” the report said. “By contrast, the family structure of lower class Negroes is highly unstable, and in many urban centers is approaching complete breakdown.”

Nearly 50 years later, the picture is even more grim — and the statistics can no longer be organized neatly by race. In fact, Moynihan’s bracing profile of the collapsing Black family in the 1960s looks remarkably similar to a profile of the average White family today. White households have similar-or worse-statistics of divorce, unwed childbearing, and single motherhood as the Black households cited by Moynihan in his report. In 2000, the percentage of White children living with a single parent was identical to the percentage of Black children living with a single parent in 1960: 22 percent.

What was happening to Black families in the ’60s can be reinterpreted today not as an indictment of the Black family but as a harbinger of a larger collapse of traditional living arrangements — of what demographer Samuel Preston, in words that Moynihan later repeated, called “the earthquake that shuddered through the American family.”

That earthquake has not affected all American families the same way. While the Moynihan report focused on disparities between White and Black, increasingly it is class, and not just race, that matters for family structure. Although Blacks as a group are still less likely to marry than Whites, gaps in family formation patterns by class have increased for both races, with the sharpest declines in marriage rates occurring among the least educated of both races.

For example, in 1960, 76 percent of adults with a college degree were married, compared to 72 percent of those with a high school diploma — a gap of only 4 percentage points. By 2008, not only was marriage less likely, but that gap had quadrupled, to 16 percentage points, with 64 percent of adults with college degrees getting married compared to only 48 percent of adults with a high school diploma.

These differences in family formation are a problem not only for those concerned with “family values” per se, but also for those concerned with upward mobility in a society that values equal opportunity for its children. Because the breakdown of the traditional family is overwhelmingly occurring among working-class Americans of all races, these trends threaten to make the U.S. a much more class-based society over time.

The striking similarities between what happened to Black Americans at an earlier stage in our history and what is happening now to White working-class Americans may shed new light on old debates about cultural versus structural explanations of poverty.

Family life, to some extent, adapts to the necessities thrown up by the evolution of the economy. Just as joblessness among young Black men contributed to the breakdown of the Black family that Moynihan observed in the ’60s, more recent changes in technology and global competition have hollowed out the job market for less educated Whites. Unskilled White men have even less attachment to the labor force today than unskilled Black men did 50 years ago, leading to a decline in their marriage rates in a similar way.

In 1960, the employment rate of prime-age (25 to 55) Black men with less than a high school education was 80 percent. Fast-forward to 2000, and the employment rate of White men with less than a high school education was much lower, at 65 percent-and even for White high school graduates it was only 84 percent. Without an education in today’s economy, being White is no guarantee of being able to find a job.

That’s not to say that race isn’t an issue. It’s clear that Black men have been much harder hit by the disappearance of jobs for the less skilled than White men. Black employment rates for those with less than a college education have sunk to near-catastrophic levels.

In 2000, only 63 percent of Black men with only a high school diploma (compared with 84 percent of White male graduates) were employed. Since the recession, those numbers have fallen even farther. And even Black college graduates are not doing quite as well as their White counterparts. Based on these and other data, I believe it would be a mistake to conclude that race is unimportant; Blacks continue to face unique disadvantages because of the color of their skin.

Most obviously, the Black experience has been shaped by the impact of slavery and its ongoing aftermath. Even after emancipation and the civil rights revolution in the 1960s, African-Americans faced exceptional challenges like segregated and inferior schools and discrimination in the labor market. It would take at least a generation for employers to begin to change their hiring practices and for educational disparities to diminish; even today these remain significant barriers. A recent audit study found that White applicants for low-wage jobs were twice as likely to be called in for interviews as equally qualified Black applicants.

Also, critically important in my view, is the changing role of women. In my first book, Time of Transition: The Growth of Families Headed by Women, published in 1975, my coauthor and I argued that it was not just male earnings that mattered, but what men could earn relative to women. When women don’t gain much, if anything, from getting married, they often choose to raise children on their own. Fifty years ago, women were far more economically dependent on marriage than they are now.

Today, women are not just working more, they are better suited by education and tradition to work in such rapidly growing sectors of the economy as health care, education, administrative jobs, and services. While some observers may see women taking these jobs as a matter of necessity — and that’s surely a factor — we shouldn’t forget the revolution in women’s roles that has made it possible for them to support a family on their own.

Women’s growing economic independence has interacted with stubborn attitudes about changing gender roles. When husbands fail to adjust to women’s new breadwinning responsibilities (who cooks dinner or stays home with a sick child when both parents work?) the couple is more likely to divorce.

It may be that well-educated younger men and women continue to marry not only because they can afford to but because many of the men in these families have adopted more egalitarian attitudes. While a working-class male might find such attitudes threatening to his manliness, an upper-middle-class man often does not, given his other sources of status. But when women find themselves having to do it all — that is, earn money in the workplace and shoulder the majority of child care and other domestic responsibilities — they raise the bar on whom they’re willing to marry or stay married to.

These gender-related issues may play an even greater role for Black women, since while White men hold slightly more high school diplomas and baccalaureate degrees than White women, Black women are much better educated than Black men. That means it’s more difficult for well-educated Black women to find Black partners with comparable earning ability

and social status. In 2010, Black women made 87 percent of what Black men did, whereas White women made only 70 percent of what white men earned. For less educated Black women, there is, in addition, a shortage of Black men because of high rates of incarceration. One estimate puts the proportion of Black men who will spend some time in prison at almost one third.

Along with many others, I remain concerned about the effects on society of this wholesale retreat from stable two-parent families. The consequences for children, especially, are not good. Their educational achievements, and later chances of becoming involved in crime or a teen pregnancy are, on average, all adversely affected by growing up in a single-parent family. But I am also struck by the lessons that emerge from looking at how trends in family formation have differed by class as well as by race. If we were once two countries, one Black and one White, we are now increasingly becoming two countries, one advantaged and one disadvantaged. Race still affects an individual’s chances in life, but class is growing in importance.

Isabell Sawhill, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution, has written extensively on the family and the economy. Her most recent book is “Creating an Opportunity Society.” This article, the eighth of an 11-part series on race, is sponsored by the W. K. Kellogg Foundation and was originally published by the Washington Monthly Magazine.